Down Street Station – Churchill’s Secret War Rooms

Down Street Station – Churchill’s Secret War Rooms

Top: Original Station Front

Present Day View

If you were to travel by subway on the Piccadilly Line, between Green Park and Hyde Park Corner in either direction, looking out the window when you’re about halfway into your journey, assuming you have an observant eye, it is possible to catch a brief glimpse of a bricked-up wall hiding the disused platform of the former Down Street Station, which as I recently discovered has some subterranean secrets to uncover.

Background History of Down Street Station

Down Street, one of the side turnings from Piccadilly was developed in the 18th century by John Downes, whose family owned land and cottages in the area for several generations, therefore; Down Street inherited their family name. Down Street Station first opened its doors on 15 March 1907 on the Great Northern, Piccadilly & Brompton Railway (GNP&BR) which makes up part of the present day Piccadilly line.

Down and Out

From the start, Down Street Station was not as successful as it was hoped it would be. There were a number of reasons for this; firstly the close proximity to two other stations, Green Park and Hyde Park Corner. Another reason was the area – Mayfair – where the local residents were often, as now, of the affluent upper classes and did not relish the thought of being seen travelling by either bus or tube. Green Park and Hyde Park had the advantage of being better placed for the tourist trade, where Down Street was out of the way. Real estate on the main Piccadilly thoroughfare was very expensive and therefore to have built the stations frontage on Piccadilly could simply not be afforded. This caused two other problems; firstly they had to build the station on a side street because it was cheaper, which meant there was not much-passing trade and people didn’t know it was there! Another reason was that Piccadilly underground runs underneath Piccadilly. Most tube lines run underneath main roads because it was cheaper, in fact, to run under roads was free. The next time you take a tube and wonder why they twist and turn all the time – this is the reason – to save money! The other drawback of building Down Street Station on a side street was the need to build longer tunnel walkways to get to the entrance of the platforms. They had to spend more money on extra tunnels and the passengers didn’t like the long walk to the platforms. Health and safety (yes even in those days) in the guise of the Board of Trade didn’t like what they saw and insisted on an extra tunnel in case of fire and for emergency evacuation. Although the railway was burdened with the extra costs, one good thing to come out of having the extra tunnel, not found in any other tube station and therefore, unbeknown at the time, would make a brilliant and unique wartime bunker.

The final nail in the coffin for Down Street was modernisation. Both Green Park (originally called Dover Street) and Hyde Park were redeveloped with escalators, it was discovered that more passengers could travel quicker on moving stairs than by lift shaft. Both these stations were upgraded with new entrances, with Hyde Park Station moving even close to Down Street, relocating underneath Hyde Park Corner roundabout. The original station entrance by the way still exists and can be seen at where the Pizza on the Park (now the Wellesley Hotel) is situated, at Knightsbridge. Down Street Station closed on 21 May 1932, after only 25 years as a station.

Mind the Six-Year Gap

Ghost stations have for a long-time been on my bucket list, so when the chance finally arrived to take the Hidden London Tour of Down Street Station, even with the ticket price set at a staggering £75 it was still worth the treat. Buying the ticket was no easy task either, as priority booking, ticket sales were sold a day earlier than the general public, but even so, it took many hours to obtain, once the online ticket sales were released the website went down for most of the day due to the heavy demand.

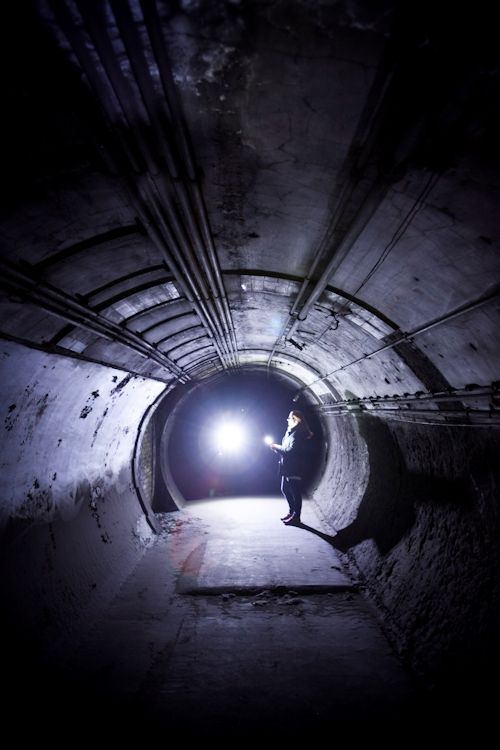

On the day of the tour, I was told to meet-up with the organisers at the Athenaeum Hotel for a safety briefing over coffee before the tour. It was explained that this tour was not for the faint-hearted, as much of the tunnel was unlit and because some of the tunnels were partitioned off for its wartime use so there are some tight spaces to get through, with walls covered in dust.

I was possibly the only one in the group who was not an underground railway anorak, although I do admit to being a Londonphile and partial to the odd ghost train ride at the fairground. There was about fifteen of us for the tour with two volunteer guides, Glen and Keith, a security guard and a lights out woman which I will explain about her task later. We were each handed torches before being admitted into a small doorway on the left-hand side of the station, where we descended down 136 steps to the bottom of a spiral staircase. The tiling inside was the traditional Leslie Green’s Edwardian coloured maroon, cream and green which was the interior design throughout the Leslie Green stations.

Guides Glen and Keith

Glen informed us that after the station was closed in 1932 there was a six-year gap when the station lay dormant until 1938, when war became inevitable and the Railway Executive Committee (REC) made up of the big four railways – Southern Railway, Great Western Railway, London North Eastern Railway and Midland and Scottish Railways and was formed to protect the essential capabilities that were vital to any war effort, mainly to move munitions and supplies by railway personnel. They needed a bombproof telephone exchange and their basement at Fielden House, Great College Street Westminster was ruled out.

Less than three weeks after the REC was formed, the Chairman Sir Ralph Wedgwood wrote to the secretary G. Cole Deacon setting out his concerns with regard to the build-up of war in Europe. The REC continued looking for a suitable location to convert for their needs. Down Street was selected as the most suitable place and formally signed a lease with London Transport (LT) on 28 March 1939.

The planned accommodation was designed to house 40 staff in a bombproof, air-conditioned (the first time air-conditioning was used by the underground) underground bunker. The site was equipped with its own telephone exchange connected to 50 telephones and a teletype machine. The postal address of Down Street was kept secret, so the post was taken to and fro by a dedicated team of four LT motorcycle dispatch team. Meeting rooms and office were provided along with washrooms, lavatories, dining facilities and dormitories. We were led by our guides through these original passageways, which were dark, narrow and smelly. Our only light was by the torches we had been provided with by the light-up lady (I mentioned earlier). Every time we arrived at a certain point in our station tour we were given the order; “Light’s Out” so as not to distress or distract the train drivers, who were not familiar with ever seeing any lights in this particular vicinity – ever. At this point, the trains were passing by fast and furious. With howling gusts of wind you normally expect at tube stations. There is a signal positioned on the wall near the disused platform by a small door, which can be activated to change the lights from green to red instantly by operating a push-button. This was used for some of the high-ranking members of the war cabinet to summon the next available train to stop. They would board the train through the driver's cab at the front of the tube train, unnoticed by any of the passengers. I could just imagine some Hooray-Henry’s hailing a train as they would a London taxi.

Members of the British War Cabinet of all political persuasions were concerned for Winston Churchill’s safety and it was advised that the Prime Minister should himself make use of this remarkable bomb-proof shelter, in what was described as the safest place to be during the blitz. Once Churchill discovered all the meals were provided by top quality chefs from the railway hotels he was happy to work and sleep there. On 19 November 1940 Churchill dined there with some members of the REC and the war cabinet. They were served caviar, Perrier Jouet 1928 champagne, with 1865 brandy and fine cigars. Those close to Churchill would often agree that he was reluctant to shelter and he would always put the safety of others first. But he still enjoyed some of the finest of life in war-torn London!

The success of Down Street as a headquarters was demonstrated by the REC‘s decision to remain beyond the war, finally leaving on 31 December 1947, with its bomb-proof design having thankfully never been put to the test.

Down Street has returned to its previous civilian purpose of helping to ventilate the Piccadilly line, a job it still performs to this day.

Sometimes tours become available but sell like hot cakes even with the £75 price tag, which must rank Down Street of selling the world’s most expensive platform tickets.

London Time

Follow Us

The contents of this website are the property of knowledgeoflondon.com and therefore must not be reproduced without permission. Every effort is made to ensure the details contained on this website are correct, however, we cannot accept responsibility for errors and omissions.

© Copyright 2004 -

Contact Us | Advertise