A Tale of Two Centuries - The Bicentenary of Charles Dickens

“There is no writer, in my opinion, who is so much a painter and a black-and-white artist as Dickens. His figures are resurrections.” - Vincent Van Gogh.

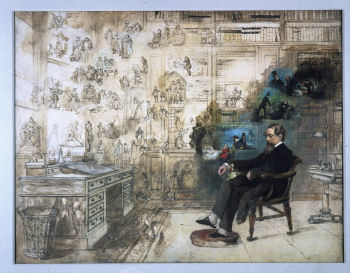

Dickens Dream, 1875 by Robert William Buss © Charles Dickens Museum

Dickens Dream, 1875 by Robert William Buss © Charles Dickens Museum

Immensely popular in his day, Charles Dickens’s stories are still as relevant and entertaining as ever, his characters are as real and exciting as they always have been. Dickens name will forever be linked to London although he wasn’t born there, he didn’t die there; however he did spend most of his working life as a writer in the metropolis of this great city. His association as a Londoner are through his many novels dealing with the squalor, hardships and everyday life of the underclass in Victorian London. Dickens and London are forever bound together, one of the same. Today, 200 years after his birth, Charles Dickens is acknowledged as the most famous London writer of all times.

“It is a silent, shady place” – (Charles Dickens, Master Humphrey’s Clock”)

10 Norfolk Street, present day 22 Cleveland Street

The Charles Dickens story is one of rags to riches. He was born on Friday the 7th February 1812 at Portsea, a suburb of Portsmouth. His father John was a clerk in the Navy pay-office attached to Portsmouth dockyard. At the age of three, Charles and the Dickens family moved to London. Their first home in the capital was at number 10 Norfolk Street, (present-day - 22 Cleveland Street) where Charles was to spend the next two years of his life. Just a few yards from their home, in the same street, stood a workhouse, which surprisingly enough, still remains (recently reprieved from demolition) it is said to be where Master Oliver Twist’s workhouse was based on. Just two years after moving in, John Dickens was posted to the Chatham Dockyards. It was whilst at Chatham that Dickens had the happiest years of his childhood, much of which he later recalled in his writings. The next time young Dickens set eyes on London again was in the winter of 1822, when his father was transferred to Somerset House in the Strand. The family arrived back in London by stagecoach, arriving at the Golden Cross, where Charing Cross stands today. They would have had to walk to their new home, as there was no other transport in those days, and a cab ride was out of their price range. Walking through Charing Cross Road, Tottenham Court Road, and Hampstead Road; finally finishing their journey at 16 Bayham Street, entering one of the smallest houses in Camden Town, in one of the poorest parts of London. Nothing of this property has survived; except for the description of the Cratchits’ home in ‘A Christmas Carol’, where the dwelling is undoubtedly modelled from.

His elder sister Fanny was beginning her four years of study at the Royal Academy of Music, whilst Charles felt his own dejection of a good education. His debt-ridden father had to move the family on to another house, this time at number 4 Gower Street North, where Dickens’s mother tried to help with the family finance by opening a school; a large brass plate on the door announced ‘MRS DICKENS ESTABLISHMENT’. Unfortunately, nobody ever came and John Dickens with such little skills in financial management was soon incarcerated within the walls of the Marshalsea Prison for Debtors.

Hard Times

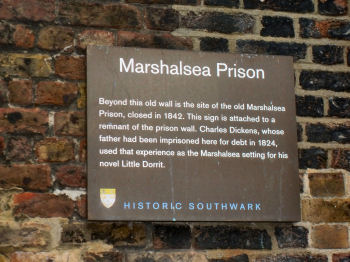

Marshalsea Prison Wall Plaque

It was during 1824 whilst John Dickens was imprisoned in Southwark for about eight months that most of the family accompanied him, with the exception of 12-year-old Charles, who broke down in tears from his despair, and rented lodgings were soon found for him in a nearby attic at Lant Street.

Young Charles was now close enough to the prison for him to have breakfast and supper with the rest of the family. The incarceration was brought to an end with the sudden death of Elizabeth Dickens, paternal grandmother of Charles, whereby John Dickens inherited £450 and was subsequently released.

The house where Charles lodged in Lant Street belonged to the Vestry Clerk of St George’s Church; the church next to the prison is still standing after recently undergoing a full restoration. Nothing however of the house in Lant Street remains, the only reminder of Dickens’s tenancy on the site, which is now occupied by an old school building, is a blue plaque.

Part of the Marshalsea Prison wall in Angel Court is still standing

At the tender age of 12 Charles, a well spoken and well brought up youngster was plunged into Warren’s Boot Blacking Company at 30 Hungerford Steps, which stood close to present day Hungerford Railway Bridge, near the Embankment Underground Station. The Thames was not embanked in those times, and the wider-river would lap against the wooden steps of Warren’s.

The Blacking factory became the inspiration for Murdstone and Grinby’s in David Copperfield. The factory is described in the novel as ‘a crazy old house with a wharf of its own, abutting on the water when the tide was in, and on the mud when the tide was out, and literally overrun with rats’.

The journey to and from work from the families temporary lodgings near Kentish Town, was done on foot. Literally, hundreds of people would walk in the same direction each morning on their way to their various workplaces. Walking was the only way to get anywhere, as there were no trains, buses, or even bicycles. Hackney Coaches were only for the very affluent in society, or for special occasions such as weddings.

Dickens suffered humiliation blackening boots in front of the window. Whilst working his mind must have been soaking up the various characters he would see every day. An older boy he worked alongside, and who took him under his wing, was Bob Fagin – his name would be used for the boss of a den of young thieves – living in a hovel off Shoe Lane.

One day Dickens got into some trouble with his bosses and was sent home, only to be taken back to Warren’s the next morning by his mother. His six shillings wages each week was still needed to help with the rent and therefore his boot blackening days needed to continue.

Hungerford Stairs, 1830 by John Harley © Museum of London

With unconcealed detestation, he describes the premises at Hungerford Stairs where the blacking factory was located. He called it: 'A crazy, tumbledown house with rotten floors and staircase, dirty and decaying, with rats swarming down in the cellar.'

He describes the misery of a child with a vivid imagination carrying out a dirty, repetitive, dreary job from morning till night, eight o'clock in the morning to six o'clock at night, ten hours a day, Monday to Saturday, washing and putting labels on thousands of pots of blacking.

Better times were on the way however, and before too long, Charles found himself eventually attending the Wellington House Academy, on the corner of Granby Terrace and Hampstead Road, where he was to be given an education. The Wellington House Academy was not a good school. The headmaster's sadistic brutality, the seedy ushers and general run-down atmosphere, are embodied in Mr Creakle's Establishment in David Copperfield.

Dickens worked at the law office of Ellis and Blackmore, attorneys, at Grays Inn, as a junior clerk from May 1827 to November 1828. Then, having learned Gurneys system of shorthand in his spare time, he left to become a freelance reporter. A distant relative, Thomas Charlton, was a freelance reporter at Doctors’ Commons, and Dickens was able to share his box there to report the legal proceedings for nearly four years. This education informed works such as Nicholas Nickleby, Dombey and Son, and especially Bleak House - whose vivid portrayal of the machinations and bureaucracy of the legal system did much to enlighten the general public, and was a vehicle for dissemination of Dickens's own views regarding, particularly, the heavy burden on the poor who were forced by circumstances to "go to law".

It was the best of times; it was the worst of times

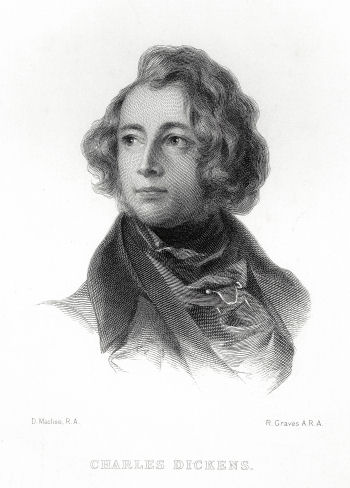

Portrait of Charles Dickens c.1849

© Museum of London

In 1830, Dickens met his first love, Maria Beadnell, thought to have been the model for the character Dora in David Copperfield. Maria's parents disapproved of the courtship and effectively ended the relationship by sending her to school in Paris.

In 1833 Dickens's first story, A Dinner at Poplar Walk was published in the London periodical, Monthly Magazine. The following year he rented rooms at Furnivals Inn becoming a political journalist, reporting on parliamentary debate and travelling across Britain to cover election campaigns for the Morning Chronicle. His journalism, in the form of sketches in periodicals, formed his first collection of pieces Sketches by Boz published in 1836. This led to the serialisation of his first novel, The Pickwick Papers, in March 1836. He continued to contribute to and edit journals throughout his literary career.

Charles Dickens's chair, at which he wrote A Tale of Two Cities

On 2 April 1836, he married Catherine Thomson Hogarth the daughter of George Hogarth, editor of the Evening Chronicle, at St Luke’s Church, Sydney Street Chelsea. After a brief honeymoon at Chalk in Kent, they set up home for a short time at number 11 Selwood Terrace, Chelsea – before moving onto Doughty Street, Bloomsbury and various other London addresses. They were to have ten children together – although their marriage was not a happy one; however, it endured for twenty-two years. Dickens formed a bond with the actresses, Ellen Ternan, which was to last the rest of his life. He separated from his wife, Catherine, in 1858 – divorce was still unthinkable for someone as famous as he was.

The Final years

Charles Dickens in his study 1859

Dickens fame grew internationally with visits to many parts of the world including America. Like a pop star of his day, he was touring and doing book readings to audiences in packed theatres.

While returning from Paris on 9 June 1865, with his mistress Ellen Ternan, Dickens was involved in the Staplehurst (in Kent) rail crash. The first seven carriages of the train plunged off a cast iron bridge undergoing repair. The only first-class carriage to remain on the track was the one in which Dickens was travelling in. Dickens tried to help the wounded and the dying before rescuers arrived. As he was leaving the train, he remembered the unfinished manuscript for Our Mutual Friend, and he returned to his carriage to retrieve it.

Ellen Ternan © Charles Dickens Museum

Dickens managed to avoid an appearance at the inquest and thus having to disclose details of him travelling with Ternan and her mother, which would have caused a scandal. Although physically unharmed, Dickens never really recovered from the trauma of the Staplehurst crash, and his normally prolific writing shrank to completing Our Mutual Friend and starting the unfinished The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Much of his time was taken up with public readings from his best-loved novels. Dickens was fascinated by the theatre as an escape from the world, and theatres and theatrical people appear in Nicholas Nickleby. The travelling shows were extremely popular. In 1866, a series of public readings were undertaken in England and Scotland. The following year saw more readings in England and Ireland.

On 8 June 1870, Dickens suffered a stroke at his at home Gad's Hill Place. He had been working all day on Edwin Drood. He came downstairs to his sitting room complaining of a toothache and then fell unconscious on the floor. The next day, on 9 June, exactly five years to the day after the Staplehurst rail crash, he died, never having regained consciousness.

Contrary to his wish to be buried at Rochester Cathedral "in an inexpensive, unostentatious, and strictly private manner," he was laid to rest in the Poets' Corner of Westminster Abbey.

Dickens was an insomniac who thought nothing of walking the London streets all night long. Through these regular excursions, he developed an encyclopaedic knowledge of London. He had what we would describe today as a photographic memory. As he walked he outlined the intricate storylines, just how his fictional characters would walk from street to street, as he followed in their footsteps across the city.

As a young lad Dickens had wanted to become an actor and had made arrangements for an audition, although unfortunately, a bad cold prevented him from taking part. All his life he was an actor at heart. He loved Shakespeare and in the late 1840’s Dickens helped raise funds to save Shakespeare’s house in Stratford-on Avon.

Dickens creations leap off the pages - you only have to call somebody a Scrooge and everyone will know exactly what you mean. Some of the names he invented came from people he knew - a neighbour, known to be a miser by the name of Goodge, and a local cheesemonger called Marley became Scrooge and Marley in a Christmas Carol.

William Sykes sold tallow and oil for lamps from a shop at 11 Cleveland Street just a few doors away from Dickens house at 22 Cleveland Street. Opposite was a cobbler named Dan Weller – who appears as Sam Weller in Pickwick Papers

After he became famous, Dickens helped popularise the term "red tape" to describe the bureaucracy in positions of power that particularly hurt the weak and poor.

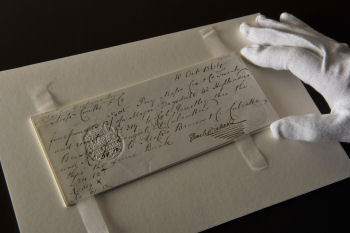

Coutts bank order signed by Charles Dickens © Museum of London

One of the things Dickens cared about most was those at the bottom. He was one of the first to offer an unflinching look at the underclass and the poverty-stricken in Victorian London. It was not until after his death that the world was made aware of his humble start in life.

If you have never read any of Dickens books, and would like to start with an easy one which you can pick up and put down, then Sketches by Boz (£8.83 from Amazon) is a good one to buy. Every chapter is a short look at London life. ‘Hackney-Coach Stands’ is an ideal chapter to start you off with.

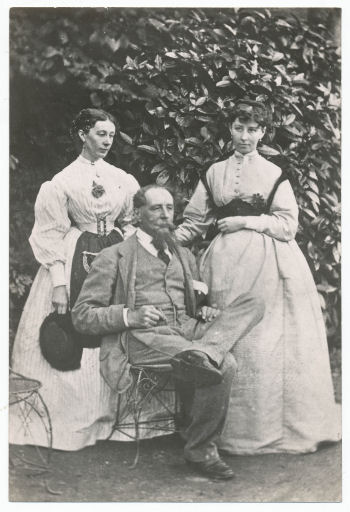

Dickens with his daughters Mary and Kate in the garden at Gad’s Hill Place,

1865 © Charles Dickens Museum

London Time

Follow Us

The contents of this website are the property of knowledgeoflondon.com and therefore must not be reproduced without permission. Every effort is made to ensure the details contained on this website are correct, however, we cannot accept responsibility for errors and omissions.

© Copyright 2004 -

Contact Us | Advertise